Executive Director of the Garfield Foundation Jennie Curtis authored this post.

It probably isn’t unusual that the personal experience of a board member would influence the grant making priorities of a foundation. In the case of the Garfield Foundation, a board member’s experience undergoing treatment for mercury poisoning led us to examine the issue.

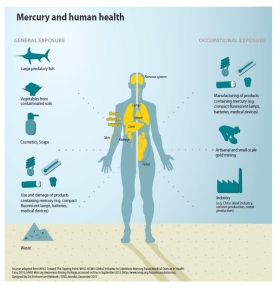

Mercury is a heavy metal pollutant that is toxic to humans and wildlife, especially to the developing nervous system. Industrial activity – such as burning fossil fuels or metal ore smelting and refining – releases mercury as air pollution which can travel long distances from the emissions source. As a result, mercury can reach places like the Arctic Circle that have no direct sources of mercury pollution, accumulating in marine mammals and fish that are a part of the global food supply.

During the last twelve years, Garfield Foundation’s approach has aimed to curb exposures by addressing the problem systemically, both domestically and internationally. In the international arena, Garfield and other donors have helped fund the Zero Mercury Working Group (ZMWG), a coalition effort that includes 98 organizations from 54 countries to reduce mercury emissions by advocating for international regulation in mercury production, trade, use and disposal. ZMWG didon the ground work in many, many countries and played an important advisory role during international deliberations. ZMWG’s successes and President Obama’s support for a mercury-export ban helped pave the way for global treaty negotiations that in January 2013 yielded the Minamata Convention on Mercury.*

At Last, A Treaty

After 4 years of intense negotiations, the Minamata Convention on Mercury is one of the first international environmental treaties agreed upon in years. It will create substantial reductions in global mercury pollution by phasing out mercury in products and processes, phasing out mercury in mining, and reducing global trade in mercury. It also requires pollution controls on new and existing coal-fired power plants and industrial boilers, waste incinerators, cement kilns and smelters.

Some key concessions were made in crucial areas to reach agreement. The result is a treaty strong in some areas but weak in others. For example, the provisions on product phase-outs are relatively strong, while the air emission control requirements for existing facilities are delayed far too long. Still, the fact that there is a global mercury treaty at all is a significant accomplishment. Overall, the agreement is a good starting point for building international coordination and cooperation, and there’s room to make improvements as treaty implementation is underway.

Critical Next Steps

During the week of October 7th, 2013, the treaty will be presented for adoption and opened for signatures at the Diplomatic Conference being held near Minamata, Japan. ZMWG will promote immediate mercury reduction activities (even before the Convention comes into force), treaty ratification, and its effective implementation.

Philanthropy can play supporting roles in assuring maximum protection for all from mercury’s toxic legacy. Some next steps include:

- Working with NGOs to obtain national mercury reduction legislation and programs, in countries such as China, Brazil, India, Nigeria, Cameroon, Lebanon, the Philippines, the United States and members of the European Union;

- Fielding a team of experts to participate in critical Convention air emission control guidance development;

- Continuing awareness raising, particularly in the developing world, to promote early Convention ratification; and,

- Influencing the agenda and the content of Convention preparatory activities to facilitate swift and strong Convention implementation.

The Garfield Foundation welcomes funder colleagues to join us on a call to discuss the challenges of treaty adoption and what’s next for moving the treaty from concept to reality on Thursday, October 24, 2013 at 3 p.m. ET/12 p.m. PT. Register here. This is an important moment during which cohesive, strategic engagement can move all of us closer than ever to a mercury poisoning-free planet.

*The Minamata Convention on Mercury was named for a disease first discovered in Minamata city in Japan in 1956. The disease was caused by the release of methylmercury in wastewater from the Chisso Corporation’s factory between 1932 and 1968. This highly toxic chemical accumulated in shellfish and fish, which, when eaten by the local populace, resulted in mercury poisoning. The excessive, unregulated mercury pollution impacted thousands of victims with symptoms including ataxia, numbness in the hands and feet, general muscle weakness, narrowing of the field of vision, and damage to hearing and speech. In extreme cases, insanity, paralysis, coma and death resulted and, a congenital form of the disease was known to affect fetuses in the womb. The Minamata situation was a shocking case of complete regulatory neglect that brought about public and international recognition regarding the dangers of mercury exposure.

Jennie Curtis is the Executive Director of the Garfield Foundation, a HEFN member, and chair of The Sustainability Funders. The Garfield Foundation recently launched a program to fund multi-stakeholder collaborative networks informed by over a decade of experience with coalitions such as the Zero Mercury Working Group and the RE-AMP Network.