HEFN Director Kathy Sessions wrote this blog post.

The Obama Administration’s new climate action plan is meeting with mixed reactions in the environmental health and justice community.

On one hand, support for climate action is a no-brainer for this field, given its bedrock values: respect for science, concern for public health, commitment to people and communities. Each new intense weather event offers painful proof that a warming planet threatens the health of people and places.

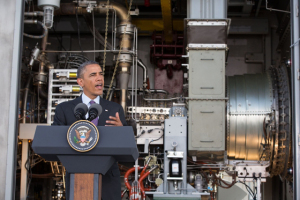

Those same values are also triggering tough questions about how well science and the public interest are reflected in the energy policies currently packaged as part of climate action. In his recent climate speech, the President focused heavily on the need to curb carbon pollution, and he touted natural gas as a cleaner energy solution. How does this square with mounting scientific concerns that methane emissions from shale gas development could pose as potent a threat as coal?

The Administration’s stated “all of the above approach to energy” raises other questions. If clean is the goal, how clean is gas – or any other source for meeting energy needs? Through an environmental health lens, one must look at a fuel’s whole life cycle – from extraction (or growth, for biofuels) to processing to transport to combustion to climate impacts and waste disposal – not just how cleanly it burns.

The “all of the above” rhetoric and current energy policy decisions do not convey the same level of priority for science and the public interest as does the new call for reducing carbon pollution and mitigating climate impacts.

The values dissonance is particularly discomfiting as the Administration simultaneously advocates protecting health and communities from climate change while promoting poorly-regulated shale gas development. HEFN is constantly hearing from funders concerned about the lack of federal regulation and adverse impacts as gas and oil fracking spreads across the U.S.

Meanwhile, as the Administration encourages expansion of gas development, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is lagging even on studies of potential hazards, much less regulation of them. The EPA, for instance, recently announced it will hand off its investigation of fracking-related water contamination in Wyoming to the state’s industry-funded research effort. An agency representative also recently signaled that the EPA’s major study of fracking impacts on drinking water, expected in 2014, will not be completed till 2016. What will happen to drinking water while drilling proceeds in the meantime?

In parallel, the President’s recent Africa trip featured announcements of a new U.S. “Power Africa” initiative. In the Administration’s words, this initiative will spread U.S. “regulatory best practices” to “responsible oil and gas resources management.” It also will boost U.S. companies’ role in expanding shale gas fracking across Africa.

The initiative was couched in inspiring language about African communities’ (serious) needs for electrification and economic development, much as the Administration has framed domestic shale gas development as part of a public climate protection plan. But what are these regulatory best practices that the U.S. will offer its African partners – and its own citizens? What safeguards – for greenhouse emissions, public health, drinking water, air quality, local control over land use – must be in place, not just in speeches, to qualify energy development as responsible? Is fracked gas the best or only choice for communities in Africa desperately seeking electrification or in the Rust Belt desperately seeking jobs?

Philanthropy and nonprofits focused on environmental health and justice values are asking questions –and asking for deeper engagement – on the energy side of the climate-energy policy agenda.

There already are calls being made to environmental funders to mobilize robust support for the Administration’s climate action plan. I believe the journey to broad-based support and climate action will have to pass through more of a town hall on energy policy. I think this would be of tremendous net benefit to the climate movement, ultimately improving solutions and strengthening the base.

Many of HEFN members’ grantees are addressing climate and energy issues already: organizing in communities, mobilizing health-focused constituencies and sectors like health care, integrating energy issues into toxics campaigns, developing science tools for development of safer chemicals and energy. Interests are converging towards strategies to move beyond all fossil fuels, especially those hard-to-reach pockets of oil, gas and coal recoverable only through heavy-impact extraction methods like fracking, mountaintop removal mining, and deep-sea drilling. The environmental health and justice movement represents a valuable base for further organizing, region by region and sector by sector, to integrate climate, energy, and other public interest concerns into solution-focused action.

I see health and environmental funders eager to move past rhetoric about a “bridge to a clean energy future” to more comprehensive consideration of energy options for a healthier climate and for healthier communities. As the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s comprehensive study of electricity generation options suggests, there is potential for more rapid exit off a dirty energy highway.

A substantial swath of the environmental health movement – including its funders – is ready to engage on climate. And on energy policy. All of the above.