Editor’s note: HEFN is pleased to share a post written by HEFN Steering Committee member Heeten Kalan in which he remembers late South African President Nelson Mandela. Within this lovely tribute to Mandela is some moving backstory on Kalan’s own journey towards justice. This post was first published in The Bay State Banner and on the New World Foundation’s blog. It is reprinted here with permission.

The local high school in my rural hometown of Louis Trichardt was for whites only, so like many of the town’s Black, Colored and Indian South African children, at the age of twelve I departed for an unknown world.

The first time I read the writings of the imprisoned South African leader of the anti-apartheid struggle was in 1983 at my new boarding school outside Johannesburg.

Nelson Mandela’s writings, which were considered illegal African National Congress (ANC) material, were handed to me secretly in a ritual at our unique, multiracial school. Custody of this contraband material rotated from student to student; one day, police arrived at the school and detained my 15-year-old schoolmate on suspicion of possessing banned books.

When I left for Canada to complete high school on a United World College scholarship, my first stop was the library where I found Mandela’s “The Struggle is My Life” along with other books banned in South Africa. I hid these books when I left the library but sitting down to read them in my dormitory, it suddenly dawned on me that I was free to read without fear or recourse. It was only years later that we would learn exactly how Mandela penned his autobiography in prison and smuggled it out in pieces to be shared with the world. How the same words on the same pages can take on different threats based on location and laws –banned in South Africa, but praised in Canada- shows the complete absurdity of apartheid. Even his image was banned in South Africa and there was a 27-year gap between the last publicly-known photo and what the world saw when he walked out of prison on February 11, 1990.

I first saw Nelson Mandela in person at the Boston Hatch Shell, while a college student in New Hampshire. A group of us rented college vans and left early in the morning to catch a glimpse of our hero when this city hosted him during his first visit to the United States in 1990. The Boston-based Fund for a Free South Africa (FreeSA), now the South Africa Development Fund, led by Themba Vilakazi worked closely with the city to host Mandela’s delegation and ensured that while he met all the prominent leaders, he also visited local churches, organizations and schools and met ordinary citizens.

His trip to Boston marks a turning point for this city: people of all races, ethnicities and social backgrounds were coming together to welcome a black man. It felt like a sign that we were capable of stepping out of the shadows of the city’s racist past. So many Bostonians had supported the anti-apartheid movement: churchgoers, students, union members, community groups, and individuals.

Churches had opened their pulpits and educational institutions their podiums. Students had cut their social activism teeth on anti-apartheid campaigns after learning of the grave indignity suffered by most South Africans. Individuals of all social backgrounds had hosted house-parties and fundraisers knowing their contribution of $10 or $10,000 was going for a good cause. Each event had its own angle on how best to dismantle apartheid and yet, at each, the refrain “Free Mandela” could be heard and echoed.

How surreal it felt to see and hear a man whose words I once read in utmost secrecy now addressing thousands of well-wishers and admirers. Many of us who fought apartheid had been fueled by both hope for a better future but also anger about the injustice. I was trying to listen for his anger, his need for revenge or even a sense of despair. Instead, his words inspired dignity, faith and hope. Here stood a man who transcended bitterness to see the potential for greater good in humanity and for a peaceful transition to a democratic South Africa. Mandela used this unique quality to keep a nation from the brink of civil war in the early 1990s and guided South Africa during this tough transition with a combination of sophisticated strategy and humble charm. His leadership style found ways to turn his adversaries into partners for peace and progress.

In 1994, I traveled to South Africa to vote for the first time and to serve as an election monitor for the African National Congress at a polling booth at the end of the street I grew up on. I assisted the elderly and disabled, including my then-56-year-old mother, to the voting booth to cast her vote for the very first time.

Days later, and right before President Mandela was to be inaugurated as our first democratically-elected leader, I walked around the Union Buildings in Pretoria which for decades housed the apartheid regime. People of all races were milling around – a visual manifestation of Mandela’s vision of South Africa’s future. I remember a conversation that day with a young Afrikaner who told me that while he did not vote for Mandela, he was willing to embrace him as President; a testament to Mandela’s amazing ability to disarm opponents and adversaries without stripping them of their humanity.

Years later I had the honor of announcing his entrance into a small celebration inside a Johannesburg hotel for Graca Machel’s, Mandela’s wife, achievements and life-long commitment to justice. Upon his arrival, you could hear a pin drop as the audience took in Mandela’s presence. Recognizing the silence as he was ushered to his seat and always the master of turning the spotlight away from himself, he yells out that he is looking for his friend Mangosuthu Buthelezi who was also in attendance.

Anyone following South African politics knows that Buthelezi was one of Mandela’s strongest critics and a long-time adversary as head of Inkatha and its affiliated political party. Mandela is then escorted to Buthelezi where he is warmly greeted with a hug and a roar of laughter between them. In that one quick move, Mandela not only broke the silence, but he found a way to share the spotlight with his adversary. It was characteristically Mandela and a move we have seen and heard of many times before. Yet it is a move that is genuine and sincere, even when calculated, and one that broke impasses for the nation to move forward.

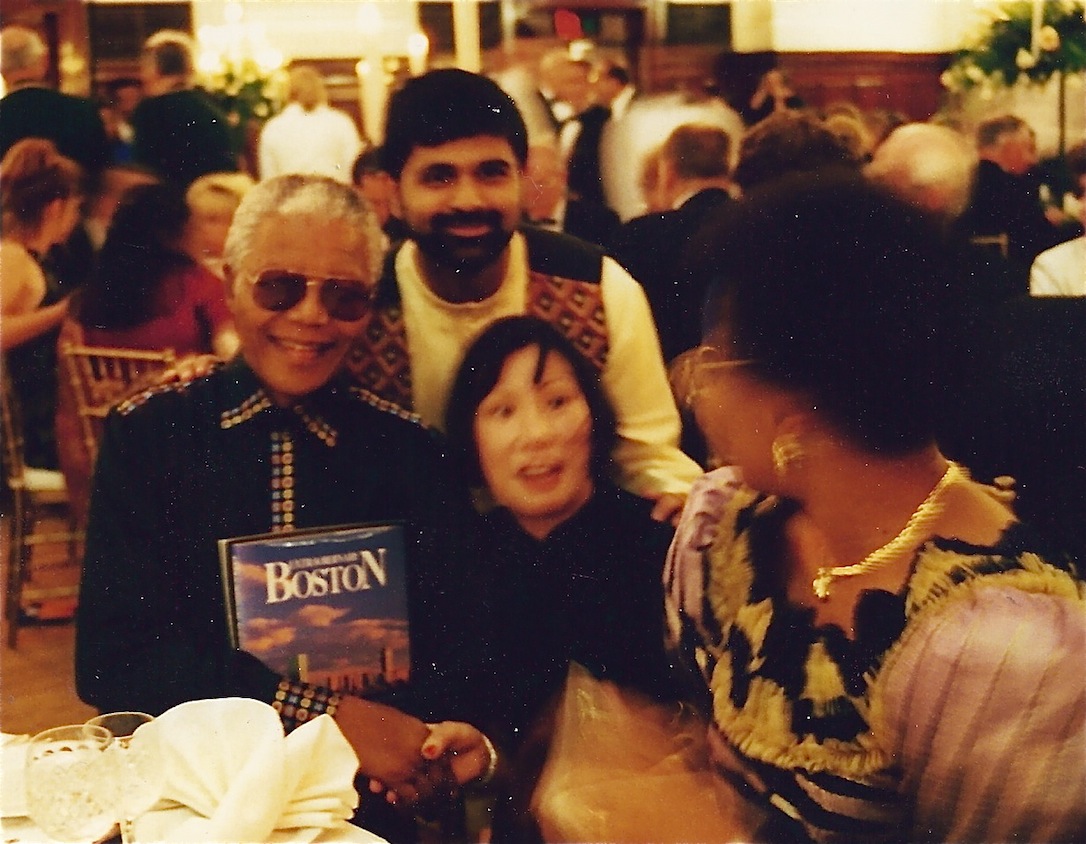

Now, with news of Madiba’s passing on Thursday, we spoke again in my family about this remarkable man. Our two sons asked me to bring out the photos I have with Mandela. One particular photo captures Mayor Menino’s representative handing over a signed copy of a book on Boston history to President Mandela at an event in South Africa. Seeing him with the Boston book in that photo was a warming reminder of that glorious and festive day at the Hatch Shell when I first saw him.

I often share Mandela’s words, once considered poison by the apartheid regime, with students of all ages. One particular message embodying both hope and vigilance resonates for our time: that we can overcome oppression and yet have to guard against becoming oppressors. That we should not be silent, nor should we become complacent.

Hamba Kahle Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela! Go Well!

Heeten Kalan is Senior Program Officer for the Global Environmental Health and Justice Fund and the New Majority Fund at the New World Foundation. He also oversees New World’s Pooled Fracking Fund, while working closely with allied funders and donors on issues related to fossile fuels and climate change.