This blog is authored by Farhad Ebrahimi, founder and chair of the Chorus Foundation, a HEFN member. It originally appeared on the Chorus Foundation blog and is reprinted here with permission.

Philanthropy isn’t necessarily known for making long-term commitments. It is, however, known for making big announcements. At the Chorus Foundation, we’ve just made a big announcement about a set of long-term commitments, and I’m really excited to be able to share the good news with you today. To borrow from our official statement for a moment:

The Chorus Foundation is pleased to announce that it has identified three frontline communities to receive eight years of grant support to speed a just transition to a regenerative economy that works for people, places, and planet.

These communities—in Alaska; Richmond, California; and Buffalo, New York — serve as inspiring examples of how communities across the country are building a new economy based on the principles of broadly shared economic prosperity, democratic governance and ownership, and climate justice.

Our commitment to each community is, at minimum, $500,000 per year in grants.

This is a really big deal for us. In addition to our pre-existing funding commitment to Eastern Kentucky, these three communities will define our grant making until we close our doors in 2023. (For those of you who don’t already know us, we’re spending down, and we only have eight years left. More on that some other time.)

It’s taken us almost a decade to get to the point where we could even consider making such long-term commitments. With that in mind, I wanted to take the time to share some of the thinking behind our decision. I’ll articulate what we’ve learned over the years, but I’m also going to advocate for a particular approach to philanthropy — one that we believe is badly needed.

ALMOST A DECADE IN THE MAKING: HOW WE GOT HERE

At its core, the Chorus story is a journey from climate, to climate justice, to what the frontline communities we support refer to as a “just transition.” In many ways, this transformation echoes the stories of the social movements that we’ve had the privilege of accompanying along the way.

Many funders seem to want to grant the money…while keeping the power. At Chorus, we believe that we should be supporting movement organizations to do what they think needs to be done.

Chorus was founded nine years ago, and I think the best word to describe our initial outlook would be “agnostic.” We knew that we wanted to support work that responded effectively to the climate crisis, but we also didn’t want to pretend that we knew what that work should look like. As we studied what most climate-driven philanthropy was supporting at the time, we saw three major themes: changes in individual behavior, market-driven energy efficiency retrofits, and a Beltway-centric push for policy. Let’s just say that the results were mixed — and that’s being extremely generous in some cases.

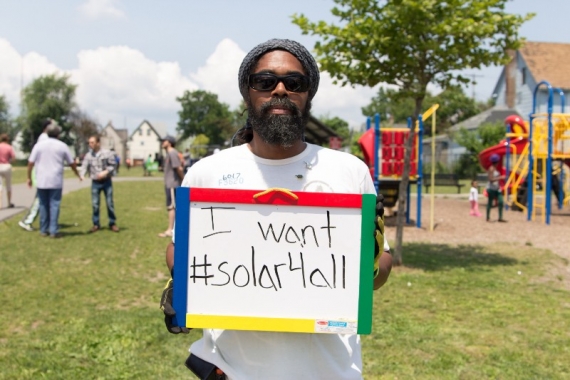

Advocating for green, renewable energy in Buffalo, NY. Image Source: PUSH Buffalo.

I would be lying if I claimed that we didn’t make some mistakes of our own. Reflecting on those mistakes, we found a different path — one that brought us to communities directly impacted by the fossil fuel industry. We learned three valuable lessons during this time period, and these lessons continue to inform our grant making. I could spend a lot of time on each of them, but for now I’ll stick to the relevant highlights:

- Large scale social change requires social movements. Organized social movements are essential to transforming the landscape of power and political will. And we’ve seen that authentic social movements have always been led by those on the front lines of crisis — in this case, the communities of color and low-income communities that are most intimately familiar with the fossil fuel industry.

- Systemic problems require systemic solutions. We understand that the climate crisis is the ecological product of an extractive system that has produced similar crises in both our economy and our democracy. If we hope to make progress on any one of these crises, then we must also address the other two.

- Place is where these things really come together. The concepts above may seem somewhat abstract, but we’ve seen that they can be fairly intuitive at the community level. It’s a lot harder to miss the inextricable nature of these systemic crises when they’re all unfolding simultaneously in your own backyard.

A JUST TRANSITION STRATEGY

The three lessons described above aren’t just a recipe for greater equity; they’re also the lens through which we evaluate strategy. This lens can be summarized in a single question: what is a place-based, social movement strategy for systemic change? We believe that a just transition strategy is exactly that.

Before we go any further, I want to emphasize that just transition is not a framework that we developed here at Chorus. We funders have a way of claiming work that we didn’t do, and so I want to be extra clear that we are incredibly indebted to the folks from Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, the Climate Justice Alliance, the Movement Generation Justice & Ecology Project, the Just Transition Alliance, the Labor Network for Sustainability, and many others for sharing their just transition thinking with us. And, of course, this is all in the context of a rich labor history that includes the visionary thinking of Tony Mazzocchi of the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union.

A truly just transition will require long-term work, and long-term work will require long-term commitments from the philanthropic community.

Here’s something that everybody knows: things have got to change. Our extractive system simply cannot be allowed to continue unchallenged. In fact, we can see that things are already changing; it’s inevitable. But justice is not inevitable, and any response to the climate crisis needs to be both timely and just. We need to be able to get from NO (what we don’t want) to YES (what we do want) in a way that respects the dignity and meets the basic human needs of everyone involved. It’s important that we understand that this is not a given; a clean energy transition is not necessarily a just one.

A just transition, then, is one that does not simply address climate change as an ecological crisis, but that addresses the political and economic inequity at its roots. This means creating an economy in which everyone can find meaningful work; an environment in which everyone has access to clean air, clean water, and a stable climate; and a democracy in which everyone has a say.

When embodied as a strategy, a just transition framework checks all the boxes:

- It has a social movement orientation. A just transition must be driven by frontline communities determining their own future, in relationship with each other, by building their collective power from the bottom up.

- It demands systemic change. Just to be perfectly clear, we’re talking about a just transition to a new political economy.

- It’s place-based. A just solution must be grounded in the lived experiences — and hence the lived expertise — of the people and places most familiar with the problem.

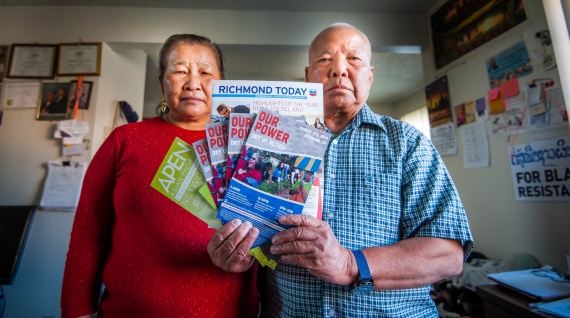

APEN leaders Seng & Lipo Chanthanasak getting ready for the Our Power Festival in Richmond. Image Source: APEN

HOW PHILANTHROPY FITS IN

This should be obvious, but obvious things have a way of going unsaid: It’s essential that we apply the same strategic lens to our own grant making. If we as funders aspire to support social movements, then we need to be providing substantial support to the grassroots organizing sector in communities of color and low-income communities.

And if we want to support work that truly reflects the importance of place, then we need to orient our grant making around place-based organizations.

But this isn’t just a question of what we support; it’s also a question of how we support it. If we want to support work that is truly transformational — rather than merely transactional — then we must first acknowledge that funders are often the biggest obstacle to transformational work. Many funders seem to want to grant the money…while keeping the power. At Chorus, we believe that we should be supporting movement organizations to do what they think needs to be done. Instead of restricted grants, which needlessly constrain complex systems to a single issue, we should be providing general operating support. Instead of short-term grants, which abandon the transformational in order to satisfy a much more transactional timeline, we should be providing long-term support.

I want to say that again for the people in the back of the room: A truly just transition will require long-term work, and long-term work will require long-term commitments from the philanthropic community. Long-term funding commitments don’t just give organizations the runway to do the work — they also free them from the annual ritual of re-application. In a culture that often fetishizes “risk,” I propose that this is an important way for funders to take on greater risk — by allocating more of our budgets long-term — on behalf of the social movements that we aim to support.

Funders hold power in many ways — including through access to information — and we need to be mindful of how we hold that power.

To show what this approach to grant making can look like in practice, we need look no further than the funding commitment that Chorus made in 2013 to Eastern Kentucky, where we’ve committed $10 million in grant support over ten years. This includes long-term, general operating support for two anchor organizations: Kentuckians For The Commonwealth, and the Mountain Association for Community Economic Development. At the same time, we still want to be nimble, and so this commitment also includes an annual grant making process to fund allied organizations and activities within the same Eastern Kentucky movement ecosystem.

Our approach to each of the three additional communities—in Alaska, Richmond, and Buffalo — will be similar, and we’re working with each community to customize a process that’s appropriate for them. All three commitments will seek to strike the same balance between long-term support for anchor organizations and flexible support for allies within their respective movement ecosystems.

We’re also interested in supporting relationships among these communities, and we want to make sure that support is attentive to their respective roles within the larger national and international context. We’re really excited to collectively learn how to best support these relationships. And we already know this: it probably won’t look like the traditional model of funder-driven convenings. This is about our grantees, not about us.

Preserving local lifeways in Alaska. Image Source: United Tribes of Bristol Bay

A FEW WORDS ABOUT PROCESS

As with most big decisions in philanthropy, ours was the product of an extended process. And, more than anything else, we are incredibly happy with the result. We will spend the next eight years working closely with four amazing communities, and we’ve learned a tremendous amount from everyone who we engaged along the way. In many ways, this has been a wonderful culmination of years of work.

All that having been said, we also know that this process was often challenging for those seeking resources, and we want to take responsibility for that.

The biggest challenge on our end was pretty straightforward: we just couldn’t fund everybody. We’d never really run anything like a “competitive request for proposals” before, and we knew that launching a process like that, with limited resources, would lead us to some very difficult decisions. In fact, we originally thought that we’d only be able to fund one or two communities in addition to Eastern Kentucky. Confronted with the gravity of the decisions that we’d set ourselves up to make, we were able to stretch and find the resources for a total of three additional communities. This felt like the right thing to do, but there nonetheless remains a tremendous amount of important work that we have found ourselves unable to support.

This is hard stuff — especially for the folks who put so much time into the process without seeing the desired result. We’ve tried to be intentional in our approach, and we’re still reflecting on what we would do differently if we were to do it all again. I believe that these reflections are as important as anything else that I share today.

First and foremost, I want to emphasize the importance of transparency in both communication and decision making. We pride ourselves in being more transparent than most, but it’s clear to us that we still have plenty of room for improvement. Funders hold power in many ways — including through access to information — and we need to be mindful of how we hold that power.

At a structural level, we also learned that this particular grant making process wasn’t the best fit for every community. The reasons are as diverse as the communities themselves: our emphasis on a just transition framework, our expectations around collaboration, our interest in integrated economic development, and some admittedly incomplete thinking about what we meant by the word “community.”

With all of this in mind, we’ve realized that we cannot simply provide opportunities for long-term support to the communities who are already most prepared to apply for that support. To truly fund with a social movement orientation, we must also provide opportunities for the kind of short- or medium-term support that would allow communities to become stronger applicants in the first place.

Building power in Eastern Kentucky. Image Source: Kentuckians For The Commonwealth

PHILANTHROPY NEEDS TO BE ORGANIZED JUST AS MUCH AS (OR EVEN MORE THAN) ANYBODY ELSE

It should come as no surprise that there is much, much more just transition work out there than one foundation can support.

With that in mind, we strongly believe that we must redouble our commitment to organizing the philanthropic community itself. We need to be reaching out to other funders — both to advocate for just transition as a strategy, as well as to coordinate our funding efforts where such alignment already exists.

Now you understand why I sat down to write this piece in the first place. GOTCHA. If any of these ideas resonate, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us — including but not limited to commenting on this post. And please keep your eyes peeled for more writing on my part; I’ve only just begun to scratch the surface. Seriously, just ask our communications team: the first draft was waaaaay longer.

Thanks for reading. We’re excited to take this journey together!

Farhad Ebrahimi is the founder and Board President of the Chorus Foundation. He is on the boards of directors of the New Economy Coalition, Citizen Engagement Lab, Democracy Alliance, and Divest-Invest.